Across England and Wales there is a vast area within our sewer network that is unknown to us. Unmapped, the condition and location of these sewers presents a significant challenge to water companies. WRc Principal Consultant Peter Henley explores the technology that is now making it possible to start visualising and responding to previously unknown sewer systems.

In England and Wales, water companies face a unique challenge: it is estimated that over 155,000 miles of sewer is invisible.

As long as these pipes remain unmapped, effective maintenance remains problematic for a number of reasons. It is more difficult to respond to reports of blockages and more challenging to introduce preventative measures around reducing the number of pollution and collapse incidents. Currently, when a water company receives a blockage call out, if the sections of sewer involved are unmapped, they will need to send their teams to investigate and while there, the engineers will map these sewers and incorporate the maps into their own records. This localised reactive mapping, if continued at its current rate, is expected to take 80 years to completely cover the unmapped network. As estimates reveal that 60–70% of reported pollution incidents are caused by blockages and that these are found primarily close to the property side, this makes the mapping exercise a pressing issue.

In the context of leakage, flooding and blockages, 80 years is a long time: too long to enable us to effectively manage the challenges facing us now and which will only get worse as the impacts of climate change are felt in the UK. A quicker, more efficient means of conducting this work needs to be found, especially so, as we anticipate a housing boom feeding more properties into the system.

To contend with this challenge, advances in technology in recent years have opened opportunities to begin mapping these sewer systems more effectively. Over the last three to four years, businesses such as WRc have been exploring how the locations of manhole covers can be used to build a picture of sewer networks beneath roads and gardens. Every manhole cover must provide an access point to the sewer below.

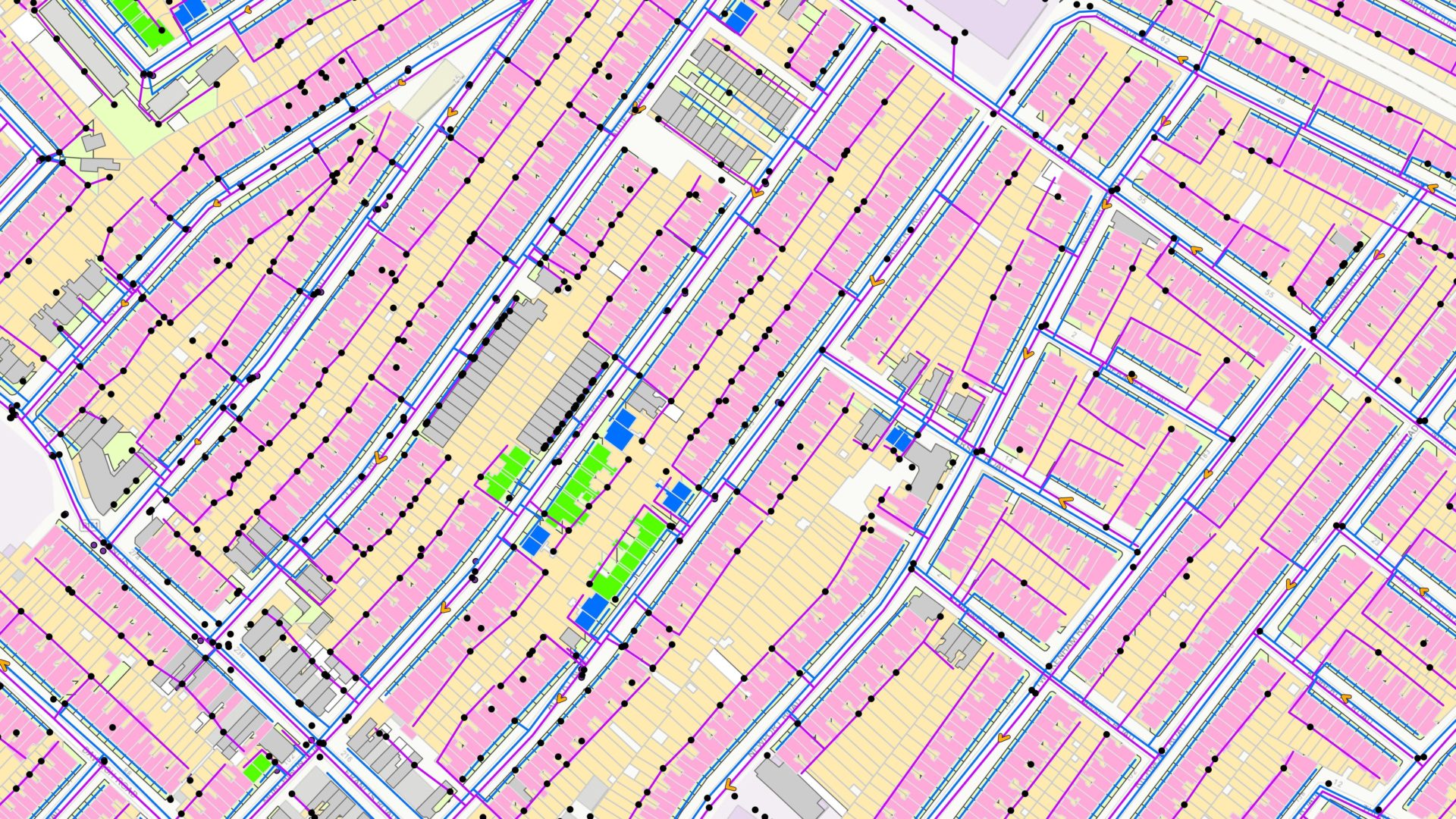

Currently, water companies are exploring the potential of aerial studies to build this picture. Modern aerial photography has developed to the extent that cameras mounted on aircraft can produce an image of high enough resolution to identify a mobile phone if it were placed on the pavement. Aerial photography advances enable a large area to be quickly captured with a picture quality sufficient to identify manhole covers and suggest the route of the sewer.

It is not as easy as a simple dot-to-dot exercise, however. Manhole covers grant engineers access to more than just the water network – they also give access to electricity, gas and internet cables. Our knowledge of the sewer system must therefore be used to interpret the images, combined with the types of houses and their known infrastructure, to infer a likely route. These inferred networks can then be overlayed on our street maps to gain a picture of these unseen systems.

At present, WRc has successfully completed a pilot programme for Thames Water to put this principle into practice. The team has mapped three 1 km2 areas of known pipework by studying aerial photography and applying knowledge and experience of the sewer systems to suggest what it believes to be the route of the networks. Through this process, the team has been able to demonstrate an 80–90% success rate of inferred sewers against what is known.

This research is showing that the technique does work in practice. But to drive this forward as a truly scalable solution that water companies can rely on to bring visibility to these unknown sections of sewer, technology is only taking us part of the way. There is still a great reliance on human knowledge and experience to turn these aerial photographs into usable references for the networks. That process is still intensive to truly scale this as a solution.

As the approach matures and technicians become more familiar with the process, could it be the case that AI can make this a viable solution? By harnessing the technical domain knowledge held by specialists, those who inform the creation of the inferred networks, WRc and its RSK partners are exploring how to train an AI solution to create the inferred networks according to the defined property age and type and then fitting this configured network to the identified drainage features such as manholes and soil vent pipes. This approach would use that same knowledge to automate the digitisation process, enabling the mapping operation to become much less intensive. This would enable our WRc engineering and data specialists to focus on reviewing and ensuring the accuracy of networks, speeding up the process and improving its accuracy.

The technology is certainly there; we now need to venture into the unknown and make it a reality.

Peter Henley is a principal consultant at WRc with 36 years’ experience in the water industry. He specialises in sewer operations as the head of pollution and flooding reduction. He is a member of the Institute of Water and was recently awarded its Pride in the South-West Award for his work in promoting the 3Ps message (poo, pee and paper only) and reducing sewer blockages.